One thing has been made extremely clear from this Portfolio: organizations are complex! No matter which metaphor you wish to use, you have to accept that a successful organization requires a constant flow of information and materials to a large number of people in and out of an organization. There will always be change, conflict, chaos, challenges and difficult decisions and, without understanding these complexities and the history that has led to communication in organizations today, one will never be able to understand communication today, or be able to prepare to work as a communication professional in the future.

Saturday, 12 November 2011

Saturday, 5 November 2011

Week Thirteen - Technological Processes and Changing Communication Environments

Advances in communication technology have greatly altered the way organizations communicate today compared to 100 years ago. The introduction of the telegraph in the 1800s was the first breakthrough in communication which improved the speed of communication over distances by an obscenely large amount. Since this time, technologies such as telephones, radios, televisions, computers, photocopiers, transistors, electronic mail, facsimile, the internet (and many more) have been used to improve communication in organizations.

Some advantages of these technologies include faster message transmission, being able to work from different locations, transmission to greater numbers of people (and in different locations), and communicating at different points in time (such as by email) (Miller 2009).

Two important theories exploring the use of communication in organizations are:

The Media Richness Model

In this model, there are four characteristics which show the capabilities of communication to convey information. These are:

1. The availability of instant feedback;

2. The use of multiple cues;

3. The use of natural language; and

4. The personal focus of the medium

(Miller 2009, p. 243).

If a communication channel uses many of these characteristics, it is considered rich media. Communication channels with little of these characteristics are considered lean media. It is argued that the form of communication used depends on the ambiguity of the task (ambiguous tasks require rich media (especially face-to-face communication) and unambiguous tasks require lean media) (Russ, Daft & Lengel 1990).

The Social Information Processing Model

This model suggests that the social environment in organizations, and shared meaning which ensues, has a greater impact on what communication channels are used (Schmitz & Fulk 1991). In this model, the four characteristics of deciding what communication technologies to use are:

1. The objective characteristics of the task and media;

2. Past experience and knowledge;

3. Individual differences; and

4. Social information

(Miller 2009, p. 244).

The effectiveness of the chosen communication technology depends on how it is used and appropriated (Miller 2009). A downfall to using communication technology can be the lack of visual and/or vocal/tone cues which add meaning to communication face-to-face. Furthermore, when this technology makes a person anonymous, it lowers inhibitions in communication and can lead to bullying (Kiesler 1992).

Social media is also being used in organizations. The importance of being social was exaggerated in the clip “social media on “the Office” for Small Business (Part One) – Facebook, Linked in, Twitter” watched in the lecture. However, it did demonstrate how organizations are commonly using social networking sites for communication in and out of organizations.

Luckily, new technologies do not completely replace older forms of communication, but instead aid them. However, the multiple ways to communicate today means workers are spending more and more time communicating and can therefore become less productive. Furthermore, irritations such as spam in e-mail, privacy concerns, constant updates in technology requiring teaching and learning, and the requirement of the relevant administration person to make certain software adjustments, can make communication technologies seem a hindrance at times (Miller 2009).

Changes in communication technology will be an ever-existing benefit and challenge to those communicating in organizations, and the history of these changes are vital to understanding communication in organizations today, and how this may change in the future.

*There was no tutorial for this topic*

References

Kiesler, S 1992, 'Group decision-making and communication technology', Organisational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 96-123.

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Russ, GS, Daft, RL & Lengel, RH 1990, 'Media selection and managerial characteristics in organizational communications', Management Communication Quarterly, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 151-175.

Thursday, 3 November 2011

Week Twelve - Emotion Processes and Organizational Diversity

All of the discussed approaches to communication in organizations follow logic and rationality. When employees became the focus of research (in human relations and human resources (week four)), the focus was on maximizing employee satisfaction; one small part of emotion. So now we must look at the role emotions (in general) play in organizational communication.

This leads us to Mumby and Putnam’s (1992, p. 474) idea of bounded emotionality which refers to “an alternative mode of organizing in which nurturance, caring, community, supportiveness, and interrelatedness are fused with individual responsibility to shape organizational experiences”.

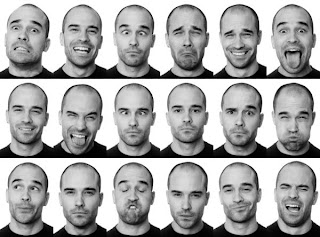

Emotion is a part of the job, and workplace relationships (Miller 2009). There are many jobs which require a specific “face”. Employees in customer service should always look happy/friendly, just like employees at a funeral home must be/look sympathetic and respectful. This acting of emotion is referred to as emotional labor, and can further be seen in managers when attempting to influence the emotions of their employees (Humphrey, Pollack & Hawver 2008).

Although it can seem obvious/straightforward when to act emotion, what emotion to act, and whom to act it to in the workplace, the complexity of emotion has led to research into emotional rules and intelligence. This research explores emotional rules, and management of these emotions (Kramer & Hess 2002; Fiebig & Kramer 1998).

Although this acting can have an effect on real emotions, it is relationships within the workforce which affect genuine emotion the greatest (whether it be liking or disliking someone, bullying, tensions or conflicting emotions in relationships) (Miller 2009).

Negative effects (which can be short- or long-term) of emotion in the workplace are stress and burnout. Please see the table below for explanation.

Effective communication is a good start to avoiding stress/burnout. If an employee understands their role, remains informed of any changes, and maintains a good relationship and level of communication with their colleagues, they are less likely to burnout or be stressed (although there are many more factors which can influence these feelings).

As discussed in the lecture, diversity (gender, age and ethnicity) can have an effect on emotion and treatment. Studies have shown that black people and women often feel less appreciated and less satisfied in their work than white males (Greenhaus, Parasuraman & Wormley 1990; Gates 2003). These are two groups which are often discriminated against and are stereotyped. Other groups often discriminated against are those with disabilities, and those with varying sexual preferences (Orbe 1998). All of the above minority groups often feel extra pressure in the workforce as they feel they are representing their group, and that others only focus on their differences (this is called tokenism) (Miller 2009).

However, the benefits of a diverse organization are starting to be recognized. By having a diverse range of employees, one can expect greater multicultural insight (which is important due to today’s globalized world), and different approaches and views which can aid in creativity, problem-solving and marketing (Cox 1991 as cited in Miller 2009).

If you want to become a communication professional in the future but are now concerned with burnout, there are strategies to help you cope. These include dealing with the causes and negative outcomes of burnout, and changing your thinking in stressful situations (Miller 2009). There is also help within organizations including social support, leave from work, and participating in decision making.

Understanding emotion in the workforce is vital to understanding communication in organizations today, as emotion plays a significant role in how people communicate, and what can happen when organizational communication is ineffective.

*There was no tutorial for this topic*

References

Fiebig, GV & Kramer, MW 1998. 'A framework for the study of emotions in organizational contexts', Management Communication Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 536-572.

Gates, D 2003, ‘Learning to play the game: An exploratory study of how African American women and men interact with others in organizations’, The Electronic Journal of Communication, vol. 13, nos. 2-3, pp. 1-18.

Greenhaus, JH, Parasuraman, S & Wormley, WM 1990, ‘Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance, evaluations, and career outcomes’, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 64-86.

Humphrey, RH, Pollack, JM & Hawver, T 2008, 'Leading with emotional labor', Journal of managerial psychology, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 151-168.

Kramer, MW & Hess, JA 2002, ‘Communication rules for the display of emotions in organizational settings’, Management Communication Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 1 pp. 66-80.

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Mumby, DK & Putnam, LL 1992, ‘The politics of emotion: A feminist reading of bounded rationality’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 465-486.

Orbe, MP 1998, ‘An outsider within perspective to organizational communication: Explicating the communicative practices of co-cultural group members’, Management Communication Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 230-279.

Orbe, MP 1998, ‘An outsider within perspective to organizational communication: Explicating the communicative practices of co-cultural group members’, Management Communication Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 230-279.

Thursday, 27 October 2011

Week Eleven - Leadership Processes and Organizational Change

Changes in organizations can happen naturally (such as growth in a new business), or they can be planned to improve productivity/effectiveness. However, if planned change is not communicated effectively to all members of an organization, it can have unexpected changes which can, at times, lead to problems.

Furthermore, people react differently to change. This can largely depend on the schema they have about the workings of an organization and how change should happen. A schema is “an organized network of already-accumulated knowledge” (Kring, Johnson, Davison & Neale 2010, p. 46). For example, when a person sees a line-up, their schema of line-ups tells them to stand at the back of the line.

Common problems in change processes include poor management support, forced change from the top, inconsistency, unrealistic expectations, lack of participation, poor communication, and ambiguity in purposes and roles (Miller 2009).

For change to be successful, communication is vital. Different ways change is communicated from management are shown in the below chart.

However, there is also unplanned change which can result from natural disasters to human error. This forced, unexpected and sudden change can often lead to crises. As stated by Wang (2008), many organizations are unprepared for crisis situations and need human resource development to help members within organizations prepare for them.

During times of change, it is important to have a leader who communicates well and leaves little or no confusion as to purposes, roles, and the changes themselves. Apart from the necessary skill of communication, people have different ideas as to what makes an effective leader. This was demonstrated during the tutorial (week 12) in which a list of 43 values relating to leadership was provided to us, and we had to choose five that we believed most important. Together the class chose 21 values.

In the complex world of organizations, it seems that it will always be impossible to please everybody. However, in times of change (specifically), it is necessary to have a skilled leader in communication.

References

Kring, A, Johnson, S, Davison, G & Neale, J 2010, Abnormal Psychology, 11th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken.

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Wang, J 2008, 'Developing organizational learning capacity in crisis management', Advances in developing human resources, vol. 10, no. 3, p 425-445.

Thursday, 20 October 2011

Week Ten - Conflict Management Processes

To demonstrate how conflict can be managed, we had to act as the mediator of a work conflict as detailed in the case study ‘The Problem with Teamwork’ (Miller 2009) in the tutorial (in week 11). Our job as mediator was not to make decisions (as would be if we were arbitrators), but to help those in conflict communicate and together resolve their issues, providing guidance where necessary (Dana 1982).

Conflict in organizations can be broken down into incompatible goals, interdependence and interaction (Miller 2009). It can be seen within groups, between groups, between individuals, or between organizations, and can cause short- and long-term complications within organizations. Common strategies to manage conflict involve avoiding the situation, accommodating (letting the other side have their way), compromising (sharing the problem), and collaborating (working together to find an optimal solution for all parties involved) (Miller 2009). Furthermore, it has been argued that responsive leadership and employee participation in decision-making helps to avoid worker-management conflict (Morrill & Rudes 2010).

Bargaining and negotiating are two other popular ways to manage conflict. These are often more formal and may be vocalized through chosen leaders of a group. They can aim to maximize one’s own gain (distributive bargaining), or the gains of both parties (integrative bargaining).

Conflict management can be influenced by one’s perceptions of the conflict and the positions of those around them (including themselves), and relationships with others (this can be linked to critical approaches (week seven) which demonstrates the importance of power in relationships). It can further be influenced by cultural factors (discussed in week six) which can lead to unsuccessful management of conflict due to different approaches being introduced in the one conflict.

Understanding how to manage conflict is vital in understanding communication in organizations today, and especially vital if hoping to work as a communication professional in the future.

References

Dana, D 1982 ‘Mediating interpersonal conflict in organizations: Minimal conditions for resolution’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, pp.11-16.

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Morrill, C & Rudes, DS 2010, 'Conflict resolution in organizations', Annual Review of Immunology, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 627-651.

Thursday, 13 October 2011

Week Nine - Decision Making Processes

Some forms of decision making are:

The Normative Model

Those at the top of the hierarchical structure formulate the problem, develop a concept, detail their options, evaluate this detail, and then implement the best solution.

Satisficing

Finding a solution that will suffice rather than finding the optimal solution (which is time consuming).

Intuition

Using intuition in times when quick decision making is necessary.

Decisions are often made in small groups using the phase model of decision making (Miller 2009). This involves getting to know each other and learning of the problem at hand (orientation), discussion of possible solutions (conflict), arriving at a consensus (emergence), and supporting of the decision by the whole group (reinforcement). However, this model suggests there is always structure and logic used.

The worst thing that can happen in decision-making in small groups is groupthink. This is when people in decision-making groups choose unanimity over discussing all and any problems to ensure the best decision is made (Callaway & Esser 1984). The case study ‘The Cultural Tale of Two Shuttles’ (mentioned in week five) is a perfect example. With the goal of launching on time and keeping the media/public happy, NASA ignored concerns, stereotyped those with concerns as unacceptable, and created an illusion of unanimity by suppressing doubts.

It has been suggested that participation in decision-making can improve job satisfaction (Jackson 1983). This has led to two models:

Affective Model

This model suggests that the simple act of involving a subordinate in decision-making will boost their esteem and self-actualization needs (seen in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – Week 4); therefore increasing satisfaction and productivity (Miller 2009).

Cognitive Model

This model stresses the importance of upward and downward flows of information by showing that subordinates (who are closer to the work) can give important information which affects decision-making. Also, through the subordinates’ participation in decision-making, implementation of decisions becomes easier.

Participation in decision-making greatly reflects ideas of human relations and human resources approaches (week four) which aim to improve employee satisfaction and productivity. However, as seen in the case study in week four, problems can arise in participative decision-making if employees feel their ideas will not be utilized, they are unsure that the extra effort is worth it (as shown in studies by Scott-Ladd & Marshall 2004), or don’t like to be doing what they consider to be the manager’s job.

This history and the linking of these approaches is important in understanding communication today.

References

Callaway, MR & Esser, JK 1984, ‘Effects of cohesiveness and problem-solving procedures on group decision making', Social behavior and personality, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 157-164.

Jackson, SE 1983, 'Participation in decision making as a strategy for reducing job-related strain', Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 3-19.

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Scott-Ladd, B, Marshall, V 2004, 'Participation in decision making: A matter of context?', Leadership & Organization Development Journal, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 646-662.

Thursday, 6 October 2011

Week Eight - Socialization Processes

Socialization processes are those processes which help an individual to adapt into a new organization. Similarly new employees may use the individualization process to adapt by making changes to better suit them.

The basic stages of the socialization process include the ideas we have before entering a new organization (anticipatory socialization), the sensemaking and understanding we go through once we enter the organization (encounter), and adjusting to fit into the organization (metamorphosis). This last stage has multiple stages within it to help complete this process including training, mentoring, interviewing, research, and relationship building.

This can be demonstrated through the case study “The Church Search” in Miller (2009) explored in the tutorial. Marsha is looking for a job as a pastor at a church, and wants to find one that fits her values and skills. From church profiles, Marsha enters into the anticipatory stage when she likes the look of a church because it is small and seems to hold similar values to her. She then enters the encounter stage when being interviewed by Nancy who informs her of the details of her new schedule. Finally we must assume that she enters the metamorphosis stage when the church helps her to integrate into the community.

The socialization process stresses the importance of information. This is achieved through interviews and other forms of communication which help employees learn of their roles, and employers learn of their employees. Effective communication here is vital as a person’s role within an organization can be very complicated if it involves many activities, or a person is managing multiple offices et cetera (Katz & Kahn 1978). This seeking of information is vital to how we communicate in organizations today.

References

Katz, D & Kahn, RL 1978, The social psychology of organizations, 2nd ed, Wiley, New York.

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Thursday, 15 September 2011

Week Seven - Critical Approaches

An important underlying thread which connects all of the approaches we have looked at is the political frame of reference. This can be broken down into three parts:

· Unitary frame of reference

There are common organizational goals, conflict is seen as negative, and power is given to management (seen in classical approaches).

· Pluralist frame of reference

There are many groups with power and varying interests, and conflict is seen as a positive (seen in systems and cultural approaches).

· Radical frame of reference

Power is very important but unequally distributed. This is related to power in society such as in legal systems and education.

An important concept in each of these frames of reference is power. There are many different ideas as to definitions of power and who holds it. This can range from whoever has information, authority, control of resources, control over gender relationships, identification with the organization, control of modes and means of production, and control of organizational discourse (Miller 2009). Haunschild, Nienhueser and Weiskopf (2009) state that “power appears as a functional medium, which is fluid, changing over time, changeable and moving from one person to the other”

There are four very important concepts which are influenced by power:

· Ideology

The ideas people have pre-conceived which influence their perceptions (Miller 2009)

· Hegemony

“class-based ‘organic’ worldviews and the production of ‘spontaneous’ consent to the ideas of the ruling classes” (Grijp 2011).

· Emancipation

Freeing people’s minds from the specific ideas that have been placed there by the influence of others (Alvesson & Willmott 1992).

· Resistance

Resistance of power

Critical approaches also take feminism into consideration including sexual harassment, women-owned businesses, women at the top of the hierarchical structure et cetera. This is demonstrated through the video ‘September Issue’ watched in the lecture about Vogue. Anna Wintour is the editor-in-chief and is a well-known and feared, powerful woman. Her power is partly explained by Robert Greene’s 48 laws (also seen in the lecture). She maintains her reputation, she keeps people dependent on her, she says less than necessary, she controls options et cetera.

The importance of power is critical to understanding communication in organizations today.

References

Alvesson, M & Willmott, H 1992, ‘On the idea of emancipation in management and organization studies’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 432-464

Grijp Pvd 2011, ‘Why accept submission? Rethinking asymmetrical ideology and power’, Dialectical Anthropology, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 13-31

Haunschild, A, Nienhueser, W & Weiskopf, R 2009, ‘Power in organizations – power of organizations’, Management Revue, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 320-325.

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Thursday, 8 September 2011

Week Six - Cultural Approaches

At this point it has become obvious that metaphors are a favorite way of explaining organizations. So here is another. Culture. But culture is hard to define. It can be argued that what separates different cultures is a mixture of values, symbols and behaviors (Miller 2009). The cultural approach therefore ties in greatly with some organizational communication challenges. For example, with globalization and changing demographics (people of different gender and ethnicity et cetera in one organization), companies are becoming less distinctive (Eisenberg & Riley 2000).

Despite the complexity of organizational culture, there are four issues which are mostly agreed on by today’s scholars: organizational cultures are complicated, emergent, not unitary, and are ambiguous (Miller 2009).

A relevant definition of culture provided by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2011, p. 1) is:

the integrated pattern of human knowledge, belief, and behavior that depends upon the capacity for learning and transmitting knowledge to succeeding generations

This definition is similar to Edgar Schein’s (1992) definition of the culture of a social group. Schein then developed his ideas into a model of culture, the three levels of which can be seen pictured below.

Schein’s model shows us that organizational culture is determined by individuals’ values and assumptions, that cultures are constantly changing to adapt to environmental contingencies, that within organizations are subcultures in which relationships can vary greatly, and that it is communication between organizational members that produces and maintains a culture.

This model was demonstrated in the case study ‘The Cultural Tale of Two Shuttles’ (Miller 2009). This compared the disasters of Challenger and Columbia, two space shuttles which ended in disastrous disintegrations, killing all crew members. In both cases, a small technical fault (which had been brought up by those lower in the hierarchical structure) caused the disasters. However, the poor NASA culture (the assumption that the opinion of those higher in hierarchical structure is more important than others, the value of launching on time and gaining good publicity, and the artifact of closed communication channels) led to the behaviors which resulted in such disaster.

References

Eisenberg, E & Riley, P 2000, ‘Organizational culture’, in Jablin, F & Putnam, L (eds), The new handbook of organizational communication: advances in theory, research, and methods, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, Calif.

Merriam-Webster 2011, Culture, viewed 5 September 2011,

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Schein, EH 1992, Organizational culture and leadership, 2nd ed. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Thursday, 1 September 2011

Week Five - Systems Approaches

The systems metaphor has replaced the machine metaphor for organizations. Instead of seeing organizations as machines which are predictable, the systems metaphor relates organizations to organisms which emphasizes the complexity and unpredictability of organizations, and how interaction with the environment is necessary for its survival.

This interaction is that of an open system. As Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1950, p. 23) states “a system is closed if no material enters or leaves it; it is open if there is import and export and, therefore, change of the components”.

Unlike classical approaches, systems approaches (as shown in Miller 2009) focus on how an organization must rely on its subsystems and supersystems to function well (hierarchical ordering and interdependence). To ensure an organization’s survival, there must be a constant exchange of information and material in and out of an organization (permeability), as well as constant feedback. Also, the complexity of the inner workings of an organization must match the complexity of the organization itself (requisite variety), or it cannot deal with external problems.

The systems theories (Cybernetic Systems Theory, Karl Weick’s Theory of Organizing, and New Science Systems Theory) together stress the importance of feedback and interdependence to reach system goals, making sense of equivocal information (information which can be interpreted in different ways) (Wagner & Gooding 1997), and the importance of complexity and chaos in organizations.

The case study (explored in the tutorial) ‘Sensemaking after the Acquisition’ (Miller 2009) is a great example of Weick’s Theory of Organizing. An independent contractor is not being provided information about what changes to expect in her role because of the change of ownership at her firm, despite reassurances that she would soon be contacted. Therefore, she cannot make sense of the equivocal information she is receiving from others and consequently panics.

Understanding the move from classical to systems approaches, the difference between open and closed systems, and the important features in each of the three systems theories are vital to understanding communication today.

References

Bertalanffy Lv 1950, ‘The theory of open systems in physics and biology’, Science, vol. 111, no. 2872, pp. 23-29.

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Wagner, JA & Gooding RZ 1997, 'Equivocal information and attribution: An investigation of patterns of managerial sensemaking', Strategic Management Journal, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 275-286.

Thursday, 25 August 2011

Week Four - Human Resources Approaches and Human Relations

The human relations and human resources approaches to organizational communication stemmed from the realization that machine metaphors were not using employees to their full potential, or making them happy. Workers were not rewarded or allowed to contribute their ideas and knowledge to the organization. This discovery was made popular from the Hawthorne studies, which then introduced us to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs theory, McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y, Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid, and Likert’s System IV (Miller 2009).

The Hawthorne studies were conducted to test how the productivity of factory workers changes in different work environments (such as different lighting, temperature, and times). Results found that the environmental factors did not change the levels of productivity, but social satisfaction from human association did. This led to uncovering the importance of the emotion and satisfaction of workers in productivity, and the importance of informal and group communication in organizational functioning (Miller 2009). This further showed how feeling/knowing you’re being watched improves productivity (Gale 2004).

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs theory was then used to learn how to motivate workers. In his pyramid (pictured below), human needs are categorized into five levels (the most important being at the base of the pyramid and then working up) in which, one cannot achieve a higher level until one has achieved the levels below it.

Following this trend, McGregor developed theories X and Y to demonstrate two polar opposites of managerial thinking. In theory X, workers are believed to be lazy, irresponsible, unintelligent, gullible and self-centered; and are therefore to be controlled using “hard” and classical approaches (McGregor 2000, p. 7). In theory Y, workers are labeled as intelligent thinkers, self-controlled, ambitious, committed, responsible, and innovative; and are to be encouraged and motivated using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

In human resources, the focus is both on employee satisfaction and concern for production. This leads us to Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid (pictured below) in which the optimal management style is team management (which shows a high concern for people and production).

This was further developed by Rensis Likert in his management systems (pictured below) in which system one is called the exploitive authoritative organization, system two is called the benevolent authoritative organization, system three is called the consultative organization, and system four is called a participative organization (Miller 2009).

Difficulties with employee participation were demonstrated through the case study of Marshall’s Processing Plant (Miller 2009) in which employee’s didn’t like attending multiple meetings and having extra work, felt like they were doing the manager’s job, or did not feel that they would truly be listened to.

Despite these complications, the above theories (which moved us away from classical approaches) help us understand how and why communication works today, and helps us prepare for working as a communication professional in the future.

References

Gale, EAM 2004, ‘The Hawthorne studies – A fable for our times?’, QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians, vol. 97, no. 7, pp. 439-449.

McGregor, D 2000 ‘The human side of enterprise’, Reflections, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 6-15.

Miller, K 2009, Organizational communication: approaches and processes, 6th ed, Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, Boston, MA.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)